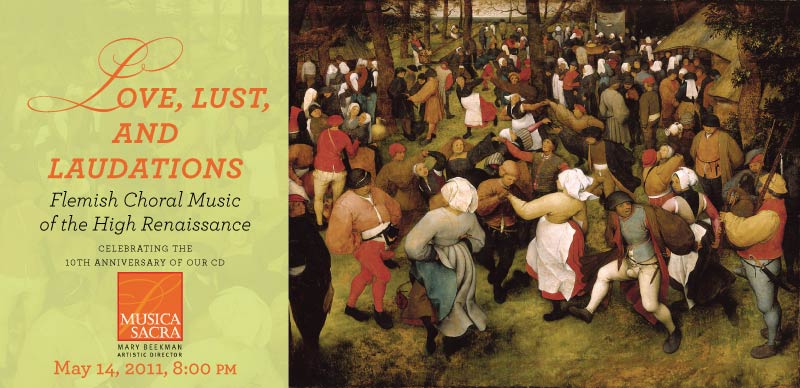

Love, Lust, and Laudations: Flemish Choral Music of the High Renaissance

Celebrating the 10th anniversary of our first recording

You’ll find it hard to believe that such ineffably beautiful sacred music could have as its counterpart some pretty explicitly profane secular music! For every transcendentally beautiful motet, there’s an earthy commentary on the baser nature of human character.

Special thanks to The Consulate of Belgium in Boston and the Belgian American Society of New England for their sponsorship of this concert.

Notes on the Performance

From Director Mary Beekman

Welcome to Musica Sacra’s final concert of our season: Flemish Choral Music of the High Renaissance. Interspersed among motets and chansons of Clemens non Papa, Orlandus Lassus and Claude Le Jeune, the three preeminent Flemish composers of the second half of the 16th century, are chansons published by the Antwerp printers, Tylman Susato and his successor, Christopher Plantin.

From the mid-15th century until the mid-16th century, composers from the Low Countries were such a dominant influence on the evolution of European musical style that in music history books this period is known as “the Age of the Netherlanders.” Indeed, the mid-sixteenth century saw the maturation of this style, heralded as a new art, or Ars Nova, by the music theorist Johannes Tinctoris in 1477. Dufay and Ockeghem initiated this style in the 1430s, and their successive compatriots, Josquin and Clemens non Papa, developed it further.

Ars Nova was indeed a new art of creating polyphonic music. It abandoned the then established contrapuntal texture of a slow moving countertenor line, quoted literally but in a much slower tempo, from plainchant or folk tunes, around which other vocal parts moved in faster note values. Composers in this modern style valued a sonority richer and more complex than that of earlier works. They achieved it through the use of a texture of four or more independent voices, relatively equal in melodic importance, of which the lowest voice acted as a harmonic support to those above it. By the mid-1500s, this technique was also informed by the Italian style—both in its declarative manner and in its use of the natural inflection of words to determine the rhythmic accents of each individual line. What made this cross-fertilization of the Northern and Southern styles possible? Netherlandish musicians were in such demand throughout the courts and churches of Europe that the Low Countries became known as “the conservatory of Europe.” As important, however, were the innovations in music printing developed by such craftsmen as Tylman Susato and Christopher Plantin, which made it possible for the works of Flemish masters to be disseminated throughout the continent.

Tylman Susato worked prolifically as a music publisher in Antwerp from 1543 until his death in the mid-1560s. His mastery of the ability to print all elements of vocal music—notes, staff, and words—in one single impression resulted in an opus of some 58 books, 25 of which were collections of chansons and 19 of which were collections of motets. When his son Jacques, who inherited his business, died in 1564, his widow sold all of the printing materials to Christopher Plantin, the most prolific and important printer of 16th century Antwerp. Although Plantin’s prints of music were but a small part of his complete printing production, they were of an extremely high quality. His presses also produced books on many divergent subjects, including numerous collections of proverbs presenting the views of the Dutch theologian Erasmus. Apparently Plantin saw music publishing as a risky venture; often he would have the composers partially subsidize the printing. Such was the case for the works heard this evening by the French composer Claude Le Jeune. Upon the death of his patron François, Duke of Anjou and brother to Henri III of France, Le Jeune received a “royal privilege” enabling him to pay Plantin for the printing of his Livre de meslanges in 1585.

The five works by Le Jeune on this evening’s program are characteristic of his secular output; they reflect both the influence of the Italian villanella style and that of L’Académie de Poésie et de Musique, an organization he joined in 1570. The villanella style attempted to imitate the simplicity of peasant music through syllabic declamations of text and strong dance-like rhythms. The Académie championed musique mesurée à l’antiqué, a poetic declamation whereby strong syllables of words would receive longer rhythmic values than weak ones. You will certainly hear all of these elements in our selections, wherein the resultant rhythmic complexity creates a dense and lively texture.

Tylman Susato was the publisher for the other composers whose works you hear this evening. Unlike Plantin, he published music exclusively, perhaps because he was also a musician. His two chansons on the program prove him to be a competent composer as well. It was he who gave Clemens his qualifying “non Papa” to distinguish him from Pope Clemens VII. However, since this pope had died in 1534 and Susato first published Clemens works in 1545, the designation was probably made in jest. Whatever the reason, the moniker remains to this day. Susato was also the first to publish the works of a young Orlandus Lassus in 1555. Lassus, although Flemish, spent much of his youth in Italy and the last thirty years of his life in Munich in the court of Duke Albrecht V of Bavaria, where he composed much of his later music, including the selections you hear tonight. It seems Lassus came to Antwerp to befriend Susato and take advantage of his new friend’s talent as a printer. The works you hear tonight are characteristic of Lassus in their employment of musica reservata. This term is used to define music that is aurally descriptive of the emotions of individual words or of the text as a whole. The opening of the motet Cantate Domino provides a perfect example: each of the two soprano parts sings a long melisma, a vocal line on one syllable, in duet on the one word cantate, which means “sing.” The motet Cum essem parvulus also demonstrates this compositional device. Its treble voices reiterate the phrase “as a child,” a literal equivalent of the words, since, in those times, boys would have sung those parts. The opening harmonic sequence of Lauda anima mea Dominum is reminiscent of that which opens the recurring choral sections of the Baroque composer Gregorio Allegri’s Miserere, just presented in our March concert. After this homophonic opening, in which all but one of the six parts declaim the text simultaneously, Lassus disperses the voices to contrapuntal imitation. The work ends with vocal entrances on every beat, providing a musical equivalent to the climactic finale in a display of fireworks.

The works of Clemens non Papa probably come closest to exemplifying Tinctoris’ Ars Nova. Of the 233 motets Clemens composed, only three use secular texts; Musica dei donum optimum is one of those three. Notice how the singers break into triple meter to declaim Musica Deo ac mortalibus. This meter celebrates that music is most pleasing to God and humans but also perhaps alludes to the Trinity of that Christian God. Adesto dolori meo, a doleful text, receives a musically pictorial setting; Clemens sets the first two lines of the psalm with melodies which descend stepwise, as though the narrator is sinking into despair. This motet typifies many of Clemens’s settings: in two parts, the motives are freely composed, not based on any preexisting music, and each part ends with the same text set to the same music. He does not use this formula in O Maria vernans rosa, however; though in two parts, the second part ends with a harmonically cascading sequence setting Amen. Clemens projects a beautiful clarity in this motet, achieved by the copious use of perfect intervals in the lines, to symbolize the purity of Mary.

Many of the composers published by Susato whose works you hear tonight are unfamiliar to modern audiences, although they were the popular composers of their day. Brass players are familiar with some of the works, especially those of Susato himself. But instrumentalists would not be privy to the texts that inspired those compositions. The texts of these works, unlike those of their Italian, French and English counterparts, speak mainly of love in its faithfulness and loyalty. Of the others, only Il estoit une fillette has the bawdy earthiness so characteristic of English and Italian madrigals. In fact, the text in its entirety was set by Janequin, revealing this segment to be by far the tamer half. The text of Notre Vicaire ung jour de fête gives us a glimpse of the strong sense of humor of the time, as well as a feeling for the laic’s skepticism regarding men of the cloth. Antoine Barbe’s Un capitaine de Pillar has an unscrupulous mercenary as its narrator, with the metaphors for battle becoming cruder as the piece unfolds. Along with Le Jeune’s Amour et Mars sont presque d’une sorte, it suggests to us that the realities and circumstances of war and battle were far more familiar to listeners of that time than to us today.

Sixteenth century Europe was a much smaller place than we in present-day America might infer from its numerous countries, languages and rulers. Flemish composers were in high demand throughout the continent, and the educated citizens of the Low Countries were aware of the developments in arts and sciences in other parts of Europe through publications made by their fellow countrymen. Sadly, however, the 1560s were the final years of the “Age of the Netherlanders.” Perhaps because of the religious wars, which divided the region in the second half of the century, the influence of Flemish musical style on the development of western music faded, never to return. Tonight, Musica Sacra presents to you the works that embody the crowning of those hundred years of Flemish musical thought.

© 2011 Mary Beekman. All rights reserved. No portion of this document may be quoted or reproduced without the author’s permission.